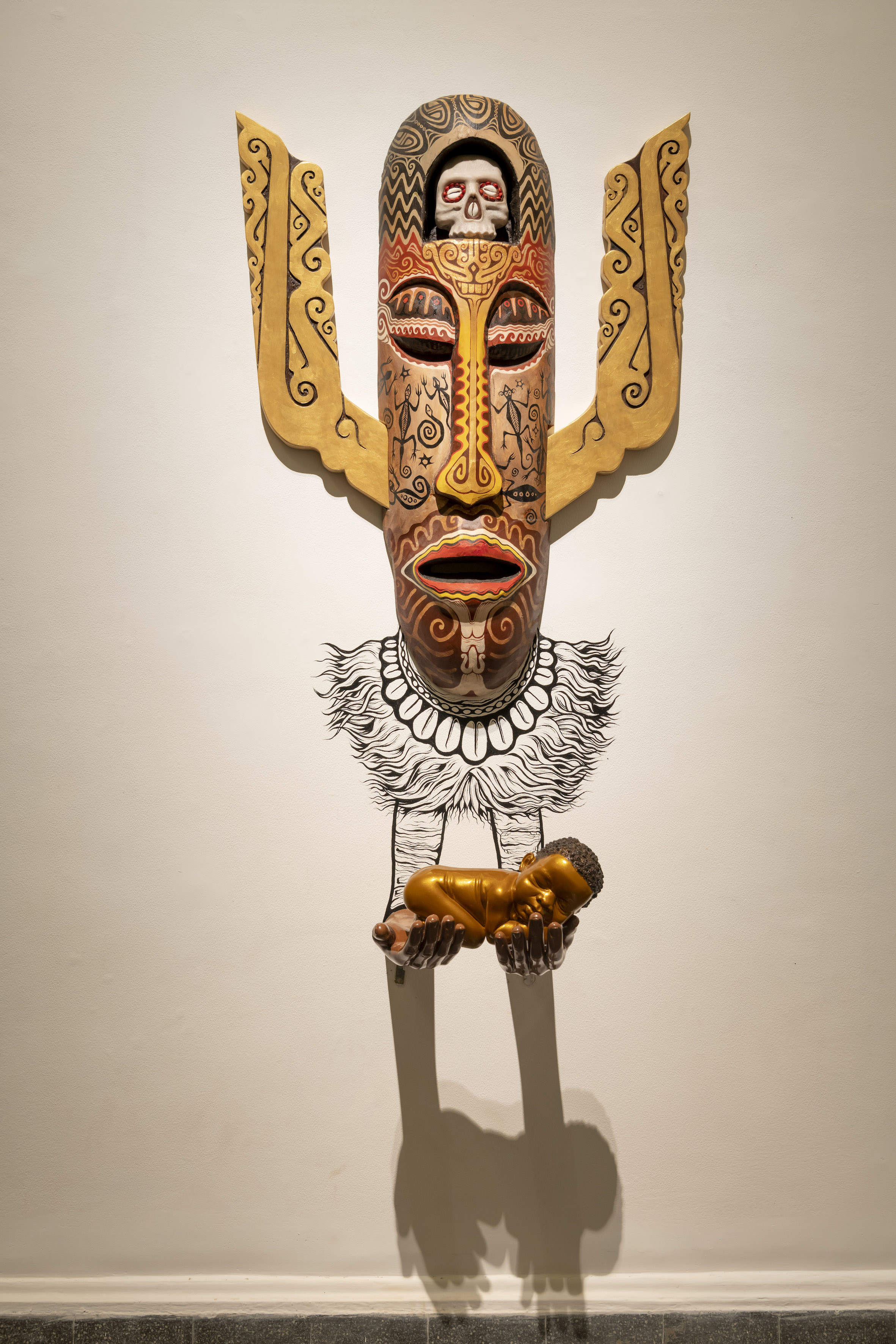

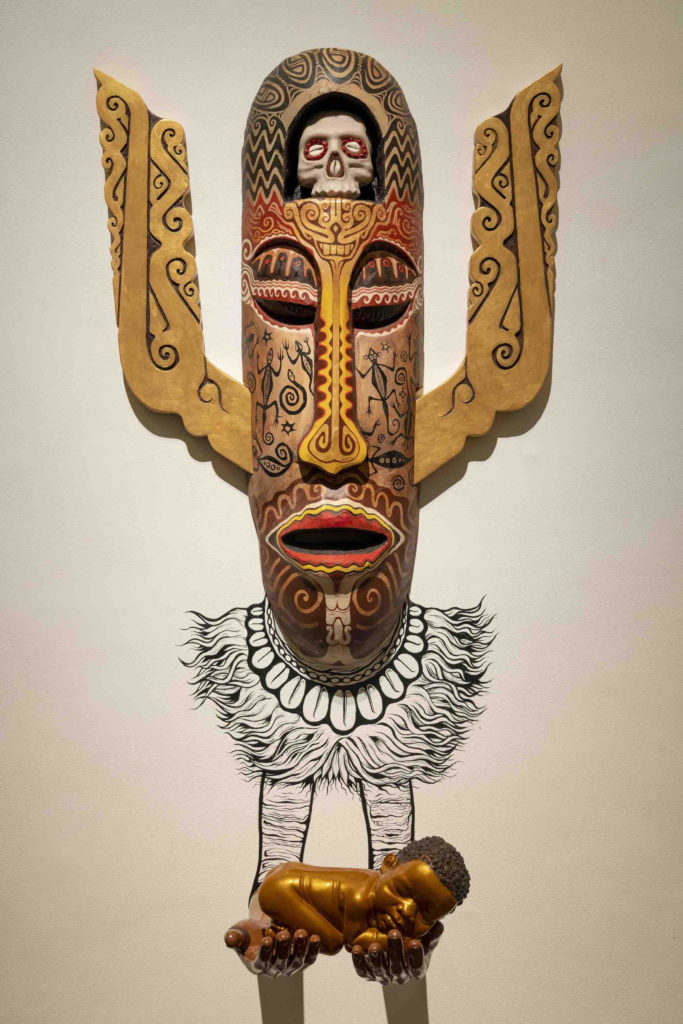

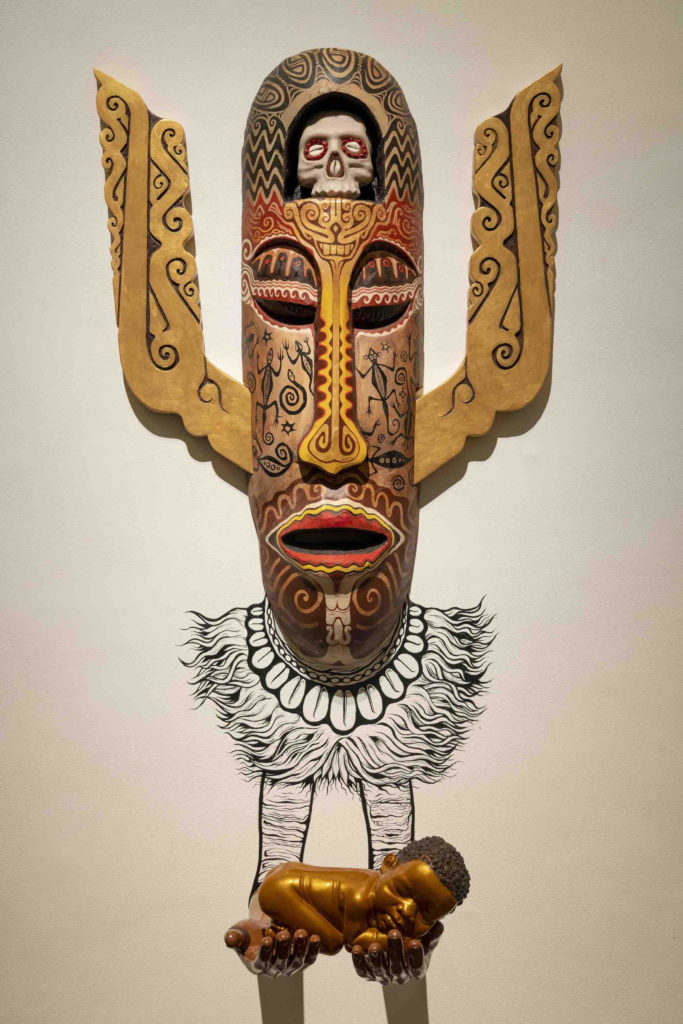

Ignasius Dicky Takndare

Ignasius Dicky Takndare

– The Hiyakhe Transfiguration, 2019

Materials: wood, paint, fiberglass

Courtesy of the artist

The Hiyakhe Transfiguration is a korwar inspired by the shape of a bird-of-paradise, which is known as “hiyakhe” in the Sentani language. The Indonesian artist Ignasius Dicky Takndare made the korwar with traditional and contemporary materials such as wood, acrylic paint, and fiberglass. Birds-of-paradise and their feathers are popular trade items that were exported to China, India, and the Arab world even before European explorers brought the first specimens to Europe. Korwar statues are usually shaped like people, but when making The Hiyakhe Transfiguration, Takndare gave his korwar bird-of-paradise wings, because the bird is a symbol for Papuan people. Takndare contributed The Hiyakhe Transfiguration to ‘Mindful Circulations’ so that the exhibition visitors could connect with the spirits of the indigenous Papuan people.

Traditionally, the indigenous people of Papua, like the Biak, use korwar to stay in touch with the spirits of their ancestors. Korwar are made after a person dies. Sometimes their skulls are incorporated in the korwar. In a study of the Biak people, the anthropologist and missionary Freerk Kamma described korwar as “soul effigies” and “spirit effigies.” To the Biak people, the anthropologist wrote, the land of souls is the place where the ancestor spirits live and where they sometimes shapeshift and return to earth disguised as humans or animal figures.

Takndare’s korwar is a hybrid sculpture that connects the past to the present. Its body, legs, and head are adaptations of the human form, but instead of arms, it has ornamented wooden wings. Traditional spirit effigies are made from wood and sometimes feature human skulls, beads, or feathers. The skull in The Hiyakhe Transfiguration is made from fiberglass and the body is decorated with acrylic paintings of natural specimens such as shells and bird-of-paradise feathers typically used by New Guinean tribes to decorate their costumes. In the local culture, as the historian Leonard Andaya puts it, the feathers have always been “associated with authority, fertility, and even invulnerability”. But the locals were not the only ones who treasured the bird pelts and their feathers.

The trade in birds-of-paradise between New Guineans, Moluccans, and other Asian traders dates back to the sixth century. The global trade in bird-of-paradise pelts and feathers peaked in the mid-nineteenth century, when the feathers were in high demand worldwide for women’s hats and other fashion accessories. A sharp decline in the availability of the bird products on the market eventually led people to believe that the birds may have become extinct.

The first steps toward their protection were taken in the second half of the nineteenth century. Under the pressure of environmentalism, the government of the Dutch East Indies prohibited hunting without a permit in 1931. The introduction of such permits was based on the “Indies Settler Nationalism” mindset, which included the argument that indigenous people did not care about their environment. “This association with settler nationalism”, the historian Robert Cribb writes, “weakened the appeal of conservationist ideas in independent Indonesia.” Nature conservation was not on the agenda of Indonesian politics before the 1970s. At present, birds-of-paradise are not facing extinction because of direct trade, but are endangered because of the loss of their rainforest habitat to plantations and the mining industry, a fate they share with indigenous Papuan people.

Takndare grew up in the 1980s and 1990s in the area around Lake Sentani in the Western part of New Guinea. He spent his childhood and youth in a town close to Jayapura, which was called Hollandia until 1962. In that year, the Dutch hesitantly transferred the sovereignty of West Papua to Indonesia. In a controversial referendum, it was decided that West Papua would not become independent, but would be a province of Indonesia. His presentation of The Hiyakhe Transfiguration in Mumbai is part of the artist’s efforts to raise awareness of the precarious situation of the indigenous people in Papua—his family and his friends.